We think that we’re the ones looking at her, but it’s she, the young black woman, who gazes at us from the cover. Before sitting down to write, I wanted to know her name, because I refuse to propagate the anonymity in which black women are generally kept in the Western world. She’s not a doll. She’s not a fetish. She’s beautiful, but she’s not just a beautiful black woman either—that’s not what defines her. I imagine her name is Isabel or Inés. Marta or Julia. In any case, a Spanish name, if she was born in Cuba. Her surnames also can orient the imagination toward towns, meadows, and vineyards in Spain. But there’s much more than Hispanic heritage in this young woman. Her gaze, inviting us to open this magazine, shouts out that other, essential part of her existence, even if there’s no trace of it in her still-unknown name. It’s a gaze that allows us to look upon her with pleasure, but in the same gesture she returns the blow and fixes her gaze on us, as if questioning us. She wants us to know. She wants us to give her a name. Let’s do it.

There’s a gaze like that on my phone screen. It’s of my great-great-grandmother, Cecilia Wilson, and it was taken at the end of the nineteenth century or the beginning of the twentieth century. Uncertainty dominates the history of people of African descent in the Americas: Precisely where in Africa were our ancestors kidnapped? What were their names, then? How did they live before being thrown into the slave ship in which they would cross the Atlantic to start their new lives as non-men, and non-women? Despite the unknown, I embrace the certainty that this photograph was taken so that my great-great-grandmother could look at me every time I turn on my phone. And so once again she recounts her story that I half-know: that the last enslaved person in my family was a very tall man dressed in white, who came from a Lucumí African tribe and lived somewhere on the eastern part of the island. One day he took to the woods bordering the river and never appeared again. There are no names, no places, no dates. However, generation after generation in the family we have believed this origin story because there’s no other option — blacks in Cuba, in one way or another, we all come from outright violence, to being nothing more than objects for labor, pieces of ebony marked with a red-hot iron on a rib, a shoulder, an arm. And they were given Spanish names. We have no exact memory of the stories of the fugitive Lucumí that were told in my family, nor of any of our African ancestors. We do, however, have memories of the flesh; and from there out to the world, in our gaze.

That former slave who escaped following the clamor of the river, travels to my era through my great-great-grandmother’s gaze on my phone screen. From the past, her eyes propel me to the future. Each day they bring the strength that a black woman must rely on. This is our history.

Slavery was officially abolished in 1886, and in 1902 the Republic of Cuba was born, following to a great extent the legacy of José Martí, for whom “Man is more than white, more than mulatto, more than black.” In reality, black Cubans, already citizens at the time, continued to be relegated to the same social inexistence and economic indigence suffered under slavery; and they had to fight for their civil rights from the early days of the Republic. Their demands would be silenced with blood; in 1912 President José Miguel Gómez ordered the killing of members of the Partido Independiente de Color and its supporters. It’s estimated that between 2,000 and 6,000 blacks and mestizos were killed in just two months.

Toward mid-century, some theories that examined and confirmed the mestizo constitution of Cubans were consolidated: poet Nicolás Guillén introduced the notion of “Cuban color” when he presented his book Sóngoro cosongo in 1931 as “mulatto verses”; and in 1940 lawyer and ethnologist Fernando Ortiz developed the concept of transculturation, creating from the melting pot the myth par excellence of national miscegenation. During those years, black Cubans’ efforts to attain certain political influence was also tenacious. Important union leaders appeared, such as Lázaro Peña, and intellectuals such as Rafael Serra and Gustavo Urrutia. The work of societies for black people —such as the Aponte and Atenas clubs in Santiago de Cuba and Havana— was also notable. They encouraged the formation of common civic and political fronts, from which to advocate for their rights.

The 1959 Revolution brought the implementation of policies that offered all Cubans, regardless of their race, equal access to health, education and culture, housing, and employment. Institutions were founded in the 1960s in which the various sectors of the population should be grouped — let’s consider the Federation of Cuban Women, the Committees for the Defense of the Revolution, and clubs for workers and professionals. As a result, the structures that had previously organized institutional life were declared obsolete. Clubs for blacks were closed, because the equality of all Cubans had been officially proclaimed: only one identity, the revolutionary one, would prevail.

Nonetheless, racial inequality did not disappear altogether.

At that time, schools proliferated where young people would be molded like “malleable clay,” aspiring to their emergence as “new men” as defined by Ernesto “Che” Guevara in 1965. Many of these centers were concentrated on a small island south of Havana called Isla de Pinos (renamed Isla de la Juventud in 1978). The first Cuban black filmmaker, Sara Gómez, arrived there, camera-in-hand, to shoot a documentary trilogy depicting the experiences of these young people. In one of them, Una isla para Miguel (1968), a scene in which Rafael, a young black man, denounces the persistence of racial prejudices within the revolutionary society, has remained anthological in Cuban cinema. Facing the camera, Rafael’s gaze, like that of the young model on the cover, interrogates us, demanding action, a real change.

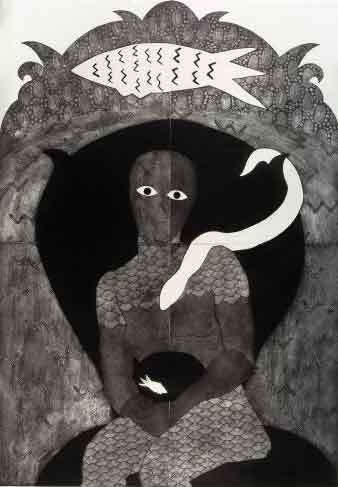

Sara Gómez is one of the maroons who never stopped fighting for social justice and who, even after her death, compels us to continue the battle. As does another great black Cuban artist, Belkis Ayón, whose work often recreated the founding myths of the Abakuá, a secret mutual aid society. From the Calabar region in West Africa comes the founding myth of the Abakuá, encoded with the discovery of the original secret —the voice of Tanze, the sacred fish— by Princess Sikan, then sacrificed and turned into a religious foundation. Since then, this society has remained closed to women, which naturally prevented Belkis Ayón from being privy to the perspective of a practitioner. Her pieces don’t reveal to us the Abakuá liturgical secret but the representation of the condition of the secret. She uses minimalist silhouettes barely revealing generic belonging, in which what’s essential is often a gaze. Furthermore, the figures lack mouths: they can’t speak. Only a thick mystery inhabits them, advancing from the hollow of the gaze towards the spectator, provoking restlessness.

Sometimes, a gaze is not even necessary. Artist María Magdalena Campos-Pons keeps her eyes closed in the polaroid series that comprise one of the pieces from When I Am Not Here, estoy allá. This message is written on her torso: “Identity Could Be a Tragedy”; but the image progressively disappears under a white spot, until it disappears almost completely in the last photo. Spectators asks themselves, what could be that “here” and “allá” (there)? — her native Cuba, the United States where the artist has lived, or Africa, which is also part of her history? The tragedy derives from the impossibility of identity, which never fully expresses everything we are.

It’s impossible to grasp the experiences of black Cuban women within a simple image, to catalog them all under an identity label. That is why we fall into a whirlwind from whose background we are absorbed by the grim look of the “Quinceañera con Kremlin,” where artist Gertrudis Rivalta alludes to a more recent reality: Cuba after the collapse of the socialist system in Eastern Europe, in the 1990s. The disappearance of economic support from the socialist bloc countries led to an acute crisis on the island, known as the “Special Period.” Since then, economic difficulties and the transformations of Cuban society have increased racial inequality, making visible a phenomenon previously circumscribed to private or family spheres. Today, the rare presence of black Cubans in spaces where the most privileged groups usually gather, attests to the undeniable existence of these inequalities.

If in the urgent daily survival there are few pathways open to the majority of blacks, we also have an invaluable capital in our maroon tradition. The maroons emancipate themselves, they don’t wait for anyone to come set them free. In the woods, they find a way to survive and defend their freedom, using whatever tools and knowledge they find along the way. They invent their own modes of subsistence.

This maronage is often transmitted by black women, from mothers to daughters, using means never mentioned in history textbooks or in famous speeches. Time and again we have sustained the home given the traditional occupations allowed to black women. María Magdalena Campos-Pons alludes to those women in “Spoken Softly with Mama,” when she reproduces old carbon plates on glass, while the artist’s ancestors seem to observe us from the bottom of the installation —always that same gaze— through photos projected on ironing boards.

The maroons continue to use whatever they find within their reach — not just to survive, but to strive. Artist Susana Pilar Delahante Matienzo created the character of Flor Elena as an avatar in the game Second Life, where she is a financial dominator (Findom). Her image was presented at the 2015 Venice Biennale in the piece “Dominio inmaterial.” The artist was able to travel there thanks to the virtual slaves of Flor Elena, who provided the funds to buy a plane ticket. The black Flor Elena, a virtual character, then had an impact on the real life of its creator, also black. Without a doubt, maroon methods. But the action is right-on; and its power, inescapable. Just like the nameless young black woman’s gaze on the cover, from which we can’t escape.