Tag: Article

The Powerful Language of Lizt Alfonso

Photos: Lizt Alfonso Dance Cuba

One of Michelle Obama’s last official acts as First Lady was to award the prestigious International Spotlight Award of the President’s Committee on the Arts and the Humanities to the Cuban dancer and dance instructor Lizt Alfonso.

It was 2016, and then-presidents Barack Obama and Raúl Castro had initiated a dialogue between their governments. The Lizt Alfonso Dance Cuba School project received the recognition at the White House for more than 25 years of work dedicated to dance, spirituality, and culture.

“During those days I confirmed that our path was the correct one, that we must fight for dreams and make them reality, especially if it means that you can make so many people happy,” Lizt tells us.

For Lizt Alfonso, Cuba is synonymous with Alma Mater, and the word dance has the same meaning as life. Perhaps that’s why her work as a dancer and choreographer has been closely linked to teaching. The company that she created in 1991 is defined as a company-school.

The Lizt Alfonso company has toured and been applauded on some of the most important stages in the world: in Tel Aviv, Israel; at the City Center and the New Victory Theater on Broadway in New York; the Shanghai Oriental Art Center in China; the Oude Luxor Theater in Rotterdam, in the Netherlands; the Thalia Theater in Hamburg, Germany; the Cairo Opera House in Egypt; and the National Auditorium of Mexico City. The home of the majority of its shows is its headquarters at the Alicia Alonso Gran Teatro in Havana.

Their dance shows have included Fuerza y compás, Elementos, Alas, Vida, Amigas, ¡Cuba vibra! and Luz Cuba. The shows are characterized by being accompanied by live music and interconnecting with other arts; they are a fusion of ballet, flamenco, and Afro-Cuban dance.

In 2015, the Company was the first Cuban dance group to perform at the Latin Grammy ceremony, alongside Enrique Iglesias, Descemer Bueno, and Gente de Zona. Together with the musicians, Lizt Alfonso’s company starred in the music video of the popular song “Bailando,” the most viewed Spanish-language music video at the time, with 29 million YouTube views.

Because of her great community work at the Lizt Alfonso Dance Cuba School and her dedication to the education of children and youth, Lizt was appointed a UNICEF Goodwill Ambassador in Cuba in 2011. In 2018, the BBC named her one of the 100 most influential women in the world.

How did that dream of teaching dance and founding a school begin for you?

When I was four years old, my mother took me to see a performance of the ballet Coppelia performed by Loipa Araújo at the National Ballet of Cuba in the Gran Teatro in Havana, in the García Lorca hall. As a little girl, I would dance whenever I heard any kind of music, and I was enchanted by that wonderful world that I discovered and decided never to leave.

I graduated from university in 1990, just when the “Special Period” began in Cuba. That happened to be the moment I was living in, but instead of complaining or sitting on my hands, I decided to make, create, invent. I was compelled personally. I felt I had a lot to say, to share and to offer, so no circumstance or person could stop me. Only my family and the dancers who believed in the project supported me. I was going against the odds.

Dance is considered a language in itself, a form of expression. What characterizes Cuban dancers? And what does the interaction with dancers from other parts of the world and such diverse audiences bring them?

Dance has allowed me to both share knowledge and enrich my own, and to travel the world. These experiences range from presenting the Company on the most important stages and events on five continents; teaching in different schools and universities; conducting workshops in dance studios and foundations; creating choreographies for other groups with different dance styles; giving lectures; and even being a jury member for national and international competitions.

Yes, dance has its own language that’s also very powerful, because it doesn’t need words to make itself understood. It’s wonderful to be able to share and interact with students from different countries, because each person is a universe, and each country they come from makes them very different because of their dissimilar life experiences. But in turn, that love for dance unites and equalizes them. It’s something magical that only the arts can achieve.

Audiences everywhere have received us excellently, whether at the Place des Arts in Montreal, or at “Fall for Dance” at City Center or at the New Victory, both in New York City … the emotional thing is that the Company has received a standing ovation everywhere. On stage, dance, hard work, discipline, doing good, and love speak for themselves, and people know how to appreciate them.

Lizt Alfonso Dance Cuba is the first Cuban company to run for an entire season at the New Victory Theater in New York. How important is that cultural exchange?

We’ve had two seasons at the New Victory Theater in New York City. The first was in 2003, and the second in 2015, each with more than 25 presentations and with resounding success. This is a very special experience. It’s a theater on Broadway, but it belongs to the 42nd Street project and it’s geared toward families. So it’s nice to see how all ages come together in the audience to enjoy the shows, just like in Havana. The first time, we presented Fuerza y Compás, and the second time, ¡Cuba Vibra! The experts who work in the theater prepare an entire program that takes children and families by the hand to discover Cuba, including its people who come from Spain and Africa, its dances and music, and even its geography. We also welcome children with special needs, who are gushing with their affection.

One day, after leaving the matinee, a group of children saw us at the subway station and began to applaud us in sign language. As I always say, art builds bridges and opens boundless doors.

The United States is a natural market for our work. Since 2001, when the Company debuted at the Summer Stage Central Park, we’ve returned almost every year and sometimes more than once a year. They’ve always received us with love, kindness, and respect. They always want us to come back, sometimes even repeating the same show—“back by popular demand,” as they say.

Despite the obvious setback in terms of cultural exchange with Cuba under the Trump administration, many people insist on bringing people closer through culture, on uniting Cubans from all sides. What would an ideal cultural relationship be like between Cubans on both shores, and between Cubans and Americans?

There are no Cubans on both shores, there are only Cubans … We are a single community, large and strong. And all we have to do is stay together, like the family we are, wherever we are. We can’t get carried away with the interests of the powers that be. We must remember that Cuba is the MOTHER who always receives us with open arms. We must work to enhance the historical culture of this blessed island, and of the times we’re living in.

We’ve already collaborated with several companies, studios, and events, and in the future we’ll do so even more, because it’s what’s logical in art and life. Collaborations and exchanges help us grow and imagine new dimensions.

When you founded the company in 1991, most of the members were women. Why was that? Do you consider dance a form of female empowerment?

When I founded the Company, the focus was directed at highlighting women and their potential. It was an opportunity to do and speak. Later we became a co-ed company, in order to be able to tell other stories. Today we can divide up into a company of women, of men, or a co-ed company.

The work with the School has several levels. It starts with vocational workshops, then children’s and youth ballet, all the way to professional dancing. It’s an enterprise that requires a tireless team to continuously improve both the technique and the preparation of each of these children and young people, from a human standpoint.

From when I created the studio up until today, many students have passed through our training. An important group of them are the professional dancers that today comprise Lizt Alfonso Dance Cuba. They live in Cuba and in many other countries around the world, and I assure you that they are all good men and women, who have carefully laid out their objectives and goals they want to achieve in life, and will surely carry them out successfully. The arts teach much more than we imagine.

As a Cuban woman who has achieved such national and international success and recognition, what keeps you up at night and what are your current priorities?

You have to get up every morning reinventing yourself and looking with certainty toward the future. The sky’s the limit, as long as life allows. I always see that wonderful things are happening, and it’s not that difficulties don’t exist—of course they exist and sometimes they’re many, and terrible—but we mustn’t let that hold us back, we must keep looking and what’s more, seeing.

- THE NEW YORK TIMES: “An amazing company with its own spirit of celebration” | Jack Anderson

- THE WASHINGTON POST: “Cuban Dance Company Dazzles at the Festival of the Arts” | Molly Ball

- THE CHICAGO SUN TIMES: “A sensual mixture of fire and spice” | Heidy Weiss

- TORONTO STAR: “Spectacular, one of the best chorus lines on this side of Broadway” | Susan Walker

- THE GLOBE AND MAIL: “Lovely! Exceptional! The stage throbs with vitality!” | Paula Citron

- CBC: “A radiant expression of the true Cuban spirit in touching music and exuberant dance” | Michael Crabb

Chucho Valdés: “Me quedo con la imaginación”

CHUCHO VALDÉS

Su mamá Pilar aseguraba que sin cumplir aún su primer año de vida ya daba señales de musicalidad. Él afirma no recordar desde cuándo toca el piano, porque desde que tiene uso de razón lo reconoce como una extensión de sí mismo. Chucho Valdés (Quivicán, Cuba, 9 de octubre de 1941) es hoy uno de los grandes pianistas de jazz del mundo.

Winner of six GRAMMY® and three Latin GRAMMY® Awards, the Cuban pianist, composer and arranger Chucho Valdés is the most influential figure in modern Afro-Cuban jazz.

El azar quiso que el pianista y compositor norteamericano Dave Brubeck1 estuviera aquella noche de 1970 entre los músicos invitados al Jamboree Jazz Festival, en Polonia, que presenciaban el concierto de un quinteto cubano de jazz, con un formato instrumental muy peculiar, liderado por un joven músico, también pianista y compositor, para más señas.

A casi 50 años de que aquel hecho, ese pianista –hoy un gigante sin edad aparente y viviendo un sosegado, pero intenso estado de creación–, no olvida el gesto de Brubeck cuando llamó la atención al mundo del jazz norteamericano sobre lo que consideró un hito singular: el aporte del joven Chucho Valdés con la incorporación de la percusión ritual afrocubana, en especial, de los tambores batá, en las manos prodigiosas de Oscar Valdés2. Poco después grabaría lo que es hoy ya un clásico del latin jazz: el disco Jazz Batá, con el propio Oscar Valdés en la percusión afrocubana y Carlos del Puerto en el bajo.3

En su disco Jazz Batá-2, Chucho parece validar aquel acto, hoy sedimentado y enriquecido, en lo que considera un estadio superior de lo que entonces fue un trascendente experimento musical.

¿Cómo ha sido presentar Jazz Batá-2 al mundo anglosajón, casi 50 años después de aquel encuentro revelador en el Jamboree Jazz de Polonia?

Cuando nos presentamos en el Jamboree Jazz Festival era la primera vez que un grupo de jazz radicado en la Isla iba a un festival internacional, y nuestro formato llamó la atención de Dave Brubeck. Renovar los elementos del jazz sin la batería era un reto. A nadie se le había ocurrido hacer un trío sin ese instrumento que parecía imprescindible. Mucha gente me dijo entonces que era una locura. Pero lo cierto es que ese atrevimiento cambió la base armónica y rítmica, usando los tambores yoruba, los batá; pero también añadimos las congas, la percusión afrocubana, y en mi opinión fue la primera vez que se creó lo que hoy llaman el set de esa percusión en los formatos de jazz. Nosotros decidimos hacerlo sin batería, aunque hoy se le incluye. Poco después, bajo este mismo concepto empezamos a trabajar en la creación y el concepto de Irakere.4

Ahora con Jazz Batá-2, que estamos presentando en conciertos por todo el mundo, el público lo recibe con asombro y complacencia, porque se da cuenta de que no hacía falta la batería en un proyecto así, y la aceptación ha sido increíble, pues es algo novedoso, que nadie había hecho antes… Usamos elementos que no están presentes en el primer disco Jazz Batá, que fue todo instrumental: ahora tenemos a Dreiser Durruthy, que es un especialista en lengua yoruba y experto bailarín –su formación académica es precisamente la danza clásica, pero domina a la perfección la folklórica– entonces, con él hemos añadido danzas y cantos legítimos en lengua yoruba. El resultado es un espectáculo de alto nivel musical.

En Jazz Batá-2 se aprecia un nuevo lenguaje de interacción entre el piano y la percusión afrocubana y, a la vez, de estos con otros instrumentos inusuales en un formato de jazz como el violín.

En Chucho Valdés se percibe siempre el disfrute candoroso ante la revelación de un descubrimiento para el cual ha trabajado mucho. Más allá de Irakere y Jazz Batá-2, ¿se plantea Chucho Valdés una continuidad en esta exploración de maridajes sonoros, a partir de lo afrocubano? ¿Qué le atrae más de estos procesos?

Es una experimentación que no acaba. Y resulta increíble, porque el piano es un instrumento melódico y armónico, canta melodías y hace armonías bellas, pero el piano es un instrumento de cuerdas percutidas, o sea, también es un instrumento de percusión. Después de mucho trabajo, de estudiar los toques de todos los orishas o santos de la religión yoruba, y los tres tambores batá –iyá, itótele y okónkolo–, tuve la idea de unir todo eso a la armonía y a la melodía. En el piano reproduzco los toques de los tres batás junto con los propios tambores batá. En Jazz Batá-2 estoy tocando percusión combinando el batá rítmico y el batá melódico, que es el piano. Ahora lo he desarrollado tanto, que no sé si habrá un disco Jazz Batá-3.

¿Cree Chucho Valdés que ya está dicho todo en el diálogo entre la percusión afrocubana y el jazz?

Pienso que estamos empezando a encontrar cosas que tenemos y que no hemos aprovechado en todas sus posibilidades. Pienso que todavía queda cerca de un 70 por ciento de todo aquello que tenemos como cultura musical de raíz, para seguir explorándolo y desarrollándolo. Esto es como un reinicio de algo que ha estado en curso. Hay toques, cantos, mucho más de los yorubas y ararás, por ejemplo, cuyas raíces están en la zona de Matanzas. También hay muchas cosas por la zona oriental, donde los ritmos son diferentes. ¡Es un tesoro lo que tenemos en Cuba! Cuando Bebo5 decidió hacer el batanga, recuerdo que se puso en contacto con Trinidad Torregrosa, para mí, el mayor batalero cubano. Iba a casa, se juntaba con Bebo y yo veía todo eso, como planearon la nomenclatura de la combinación de las congas y los batás. Bebo la escribió y ha quedado, y pienso que ahí está la clave de esa combinación. Bebo es el verdadero genio. Sabía que yo estaba intentando continuar lo que él hizo con el batanga, pero después de estudiar mucho, creo que ya el batanga quedó ahí como el origen de esta imbricación de los batás y la percusión afrocubana en el jazz, y lo que quiero hacer ahora es la continuidad.

Todo parece indicar que la imaginación de Chucho Valdés es inagotable. A estas alturas, cuando está delante del piano, ¿qué es lo que más le motiva en el proceso de imaginación y creación? ¿A qué apela para esa constante renovación y ese reinventarse sin cesar? ¿Secretos, disciplina o inspiración?

Es todo. Primero mucha información general, no solo la referida a las culturas y las músicas africana y cubana, sino a la universal. Es lo único que te permite, con una concepción muy amplia, hacer fusiones y combinaciones. Apelo también a la información que acumulo desde niño –no te olvides que crecí en un medio totalmente musical–, además de lo que investigo y busco, y todo eso lo uno a la inspiración y a la disciplina, de la que no me aparto. Tengo muchos recursos, incluido la llamada música clásica, es decir, que he tratado de tener un arsenal suficiente para la creación. Experimento mucho, hago y también deshago si veo que algo no funciona, eso lo elimino, y sigo trabajando. Para el arte de la improvisación, más que todo, lo importante es la imaginación. Sin eso no haces nada, porque no se te va a ocurrir nada si no la tienes. Beethoven tenía un alumno que daba su primer concierto y él fue a escucharlos. El alumno tocó muy bien, pero le fallaron dos notas. Al terminar fue al encuentro de su maestro, quien le dijo que había sido un concierto increíble. El alumno reconoció su error en aquellas notas, pero Beethoven le dijo: “Si te falla una nota, eso es insignificante, pero tocar sin pasión y sin imaginación, eso es lo imperdonable”. Soy un centinela del piano. Somos casi una misma cosa, inseparables. Me la paso buscando, investigando, pero no trabajo si no tengo inspiración.

En su opinión, ¿existe un jazz cubano? ¿Cómo explica su opinión al respecto?

Existe una forma muy cubana de tocar el jazz, usando nuestras raíces. Y se reconoce rápidamente, hay muchos ejemplos de los grupos que hacen este tipo de música, sobre todo entre los jóvenes. A nivel de creación, de composición, es también así.

¿Cómo ve usted la salud del piano en el jazz que se hace en Cuba? ¿Hay relevo, continuidad o estancamiento?

Estamos en el mejor momento de nuestra historia pianística, porque lo que está pasando con los pianistas cubanos es un verdadero fenómeno. Digo que se acabaron los pianistas mediocres, eso es una especie extinguida en Cuba. Todos tocan bien. Son muchísimos, pero siempre hay quienes destacan más, y por favor, que no se molesten los que no aparezcan, podría ser más un olvido que una omisión. Esto comenzó desde una generación anterior, en la que los nombres más prominentes fueron Emiliano Salvador y Gonzalo Rubalcaba –dos grandes–, y le siguieron Hilario Durán, Omar Sosa –uno de los más originales e imaginativos, lo admiro mucho–, Ernán López-Nussa… Y después viene la generación actual, que está arrasando: Rolando Luna, Harold López-Nussa, Kemel Roig, Aldo López-Gavilán –que puede tocar cualquier cosa–, David Virelles –para mí es un genio–, Iván “Melón” Lewis –es de los bravísimos–, Pepe Rivero – increíble–, Alejandro Falcón, Miguel Núñez, Alfredo Rodríguez Jr. y eso no se detiene ahí: entre los más jóvenes hay ya quienes destacan como Leyanis Valdés y un muchacho que se llama Víctor Campbell, que va a ser una revolución en el piano.

Y tengo necesariamente que coincidir con Beethoven en algo que conecta con todas las generaciones: la técnica es muy importante, pero entre la técnica y la imaginación, me quedo con la imaginación.

- Dave Brubeck (Concord, California, 6 de diciembre de 1920-Norwalk, Connecticut 5 de diciembre de 2012).

- Oscar Valdés Campos. Percusionista, cantante y pedagogo. Fundador del grupo Irakere. Actual director del grupo Diákara (La Habana, 12 de noviembre de 1937).

- Carlos V. del Puerto. Bajista, contrabajista y pedagogo. Fundador del grupo Irakere (La Habana, 1951).

- Irakere, orquesta fundada por Chucho Valdés en 1973, es una de las bandas más influyentes de latin jazz.

- Se refiere a su padre, Bebo Valdés (Dionisio Ramón Emilio Valdés Amaro: Quivicán, 9 de octubre de 1918-Estocolomo, Suecia, 22 de marzo de 2013), uno de los más prominentes directores orquestales, pianistas y compositores de música popular cubana.

Notas

Havana at 500

Photos: Otmaro Rodríguez

Havana, this bustling and talkative city —so well captured by visual artists René Portocarrero and Luis Enrique Camejo— is maritime, open and unprejudiced, yet has its own unique inner life. It’s a city with every style and no style, “a style without style that, in the long run, through a symbiotic or amalgamative process, takes on a particular baroqueness that functions as a style,” as the great Cuban novelist Alejo Carpentier wrote.

It’s a baroque city in that it’s heterogeneous and disjointed, “shy, sober, almost hidden,” built on a human scale, whose architecture never dwarfs man. This is the case in its historic center and also in more modern areas of Havana where skyscrapers, sometimes impersonal, don’t block out the sun or prevent the sea breeze from passing through.

Five centuries after it was founded, Havana is among the Latin American cities that best preserves its historical legacy and its colonial core. The foundational center of the city, in so-called Old Havana, is one of the most important urban complexes in the region. There you can see 88 monuments of historical-architectural importance, 860 of environmental importance, and 1,760 harmonic buildings, some corresponding to the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. It’s a monumental zone par excellence.

Visitors may think they’re visiting a museum—a living museum, amidst offices, schools and commercial establishments, in an area with some 100,000 residents. The restoration process in Old Havana, years in the making, has managed to avoid turning it into a static zone, dedicated to contemplation; rather it’s being preserved and revitalized as a dynamic urban area in which housing, cultural, and tourist elements coexist harmoniously.

El Vedado is the best area of modern Havana, one of the most coherent manifestations of contemporary urbanism. While there are damaged areas there, like in other parts of the city, it’s the most coveted residential area for habaneros.

According to architect Mario Coyula, so much value is placed on Old Havana that there’s a risk of thinking that the rest of the city doesn’t have much to offer. For him, more than half of the city has architectural value given the various styles and trends from all eras.

“The essence of Havana is the concert that it puts on of its own volition, and the most important element is the scale—the rhythm that light and shadows play on its facades,” adds Coyula. In his opinion, there are two emblematic buildings in the city: the Palace of the Captains General in Old Havana, and Las Ruinas restaurant, in Lenin Park, on the outskirts of the capital.

Havana is Cuba’s main tourist destination—it’s where you can find the big hotels, the glittering cabarets, the most famous restaurants, and a strip of beaches east of the city that stretches over ten kilometers of white and fine sand and crystal-clear ocean.

The city also excels at culture: it’s a great mosaic where the Spanish and African influence combine to engender their own identity. About 40 first-rate museums open their doors here and Havana’s international fairs and film, book, music, arts and ballet festivals attract specialists and curious people from all over the world. The university, founded in 1728, is very prestigious and its medical and scientific institutions enjoy recognition far beyond the island.

The sanctuaries of the three most revered saints by Cubans are in the capital: San Lázaro, patron saint of dogs and wooden crutches, the leper of miracles; Santa Bárbara, in the humble neighborhood of Párraga; and the Virgen de Regla, the black saint in the blue cloak who carries a white child in her arms. These deities are identified in the Santeria religion, respectively, as Babalú Ayé, Shangó, and Yemayá, mother of all orishas.

Havana, with its Santeria drum ceremonies and its coconut pieces thrown at random to read the future and other African rites. Where, sometimes, in the same house it’s possible to find attributes of both Palo Monte and Santeria, and images of Christian deities.

Havana, of rumbas de cajón and leather sandals, of great carnival revelry and spontaneous neighborhood house parties.

Many claim that Havana is one of the most beautiful cities in the world. Ernest Hemingway, the famous American novelist who lived here during the final years of his life, said that only Venice and Paris surpassed the Cuban capital in beauty. It’s possible. For now, we can say for sure that the light of the tropics, nights on the Malecón—the most popular and cosmopolitan place in the city—, and habaneros’ friendly smiles, among other charms, win over visitors for years to come. The view of the city from El Morro at sunset is an unforgettable sight.

At the end of the sixteenth century, in view of its favorable geographical position, someone defined Havana well, calling it the “Key to the New World.” The German savant, Alexander von Humboldt, whom Cubans consider the country’s second discoverer, saw it as the most cheerful, picturesque and charming of cities. A poet once exalted Havana as a woman with three rival lovers: the sun, the sea and the sky. Another poet, after laying eyes on its portals and columns, its parks and squares and, above all, its forgotten and hidden corners, waxed on about the city of dreams, built of clarity and seafoam.

According to lore, the first mass was held and the first town hall was built in the shade of a ceiba tree on the northwest side of what would become the Plaza de Armas. El Templete, a monument dating from 1828, commemorates the founding act of the town.

In Afro-Cuban religions, the ceiba tree is sacred. Blacks coming from Africa as slaves entrusted their legend in it. For the believers, their ancestors, Catholic saints, and many spirits have settled in that tree over time. The ceiba is treated as a saint and cannot be cut, burned, or otherwise removed without permission from the orishas.

Legend has it that if you circle the ceiba tree at El Templete three times, you’ll be granted whatever you wish for. This is the welcoming and generous spirit of Havana.

Gazes of the Black Woman

We think that we’re the ones looking at her, but it’s she, the young black woman, who gazes at us from the cover. Before sitting down to write, I wanted to know her name, because I refuse to propagate the anonymity in which black women are generally kept in the Western world. She’s not a doll. She’s not a fetish. She’s beautiful, but she’s not just a beautiful black woman either—that’s not what defines her. I imagine her name is Isabel or Inés. Marta or Julia. In any case, a Spanish name, if she was born in Cuba. Her surnames also can orient the imagination toward towns, meadows, and vineyards in Spain. But there’s much more than Hispanic heritage in this young woman. Her gaze, inviting us to open this magazine, shouts out that other, essential part of her existence, even if there’s no trace of it in her still-unknown name. It’s a gaze that allows us to look upon her with pleasure, but in the same gesture she returns the blow and fixes her gaze on us, as if questioning us. She wants us to know. She wants us to give her a name. Let’s do it.

There’s a gaze like that on my phone screen. It’s of my great-great-grandmother, Cecilia Wilson, and it was taken at the end of the nineteenth century or the beginning of the twentieth century. Uncertainty dominates the history of people of African descent in the Americas: Precisely where in Africa were our ancestors kidnapped? What were their names, then? How did they live before being thrown into the slave ship in which they would cross the Atlantic to start their new lives as non-men, and non-women? Despite the unknown, I embrace the certainty that this photograph was taken so that my great-great-grandmother could look at me every time I turn on my phone. And so once again she recounts her story that I half-know: that the last enslaved person in my family was a very tall man dressed in white, who came from a Lucumí African tribe and lived somewhere on the eastern part of the island. One day he took to the woods bordering the river and never appeared again. There are no names, no places, no dates. However, generation after generation in the family we have believed this origin story because there’s no other option — blacks in Cuba, in one way or another, we all come from outright violence, to being nothing more than objects for labor, pieces of ebony marked with a red-hot iron on a rib, a shoulder, an arm. And they were given Spanish names. We have no exact memory of the stories of the fugitive Lucumí that were told in my family, nor of any of our African ancestors. We do, however, have memories of the flesh; and from there out to the world, in our gaze.

That former slave who escaped following the clamor of the river, travels to my era through my great-great-grandmother’s gaze on my phone screen. From the past, her eyes propel me to the future. Each day they bring the strength that a black woman must rely on. This is our history.

Slavery was officially abolished in 1886, and in 1902 the Republic of Cuba was born, following to a great extent the legacy of José Martí, for whom “Man is more than white, more than mulatto, more than black.” In reality, black Cubans, already citizens at the time, continued to be relegated to the same social inexistence and economic indigence suffered under slavery; and they had to fight for their civil rights from the early days of the Republic. Their demands would be silenced with blood; in 1912 President José Miguel Gómez ordered the killing of members of the Partido Independiente de Color and its supporters. It’s estimated that between 2,000 and 6,000 blacks and mestizos were killed in just two months.

Toward mid-century, some theories that examined and confirmed the mestizo constitution of Cubans were consolidated: poet Nicolás Guillén introduced the notion of “Cuban color” when he presented his book Sóngoro cosongo in 1931 as “mulatto verses”; and in 1940 lawyer and ethnologist Fernando Ortiz developed the concept of transculturation, creating from the melting pot the myth par excellence of national miscegenation. During those years, black Cubans’ efforts to attain certain political influence was also tenacious. Important union leaders appeared, such as Lázaro Peña, and intellectuals such as Rafael Serra and Gustavo Urrutia. The work of societies for black people —such as the Aponte and Atenas clubs in Santiago de Cuba and Havana— was also notable. They encouraged the formation of common civic and political fronts, from which to advocate for their rights.

The 1959 Revolution brought the implementation of policies that offered all Cubans, regardless of their race, equal access to health, education and culture, housing, and employment. Institutions were founded in the 1960s in which the various sectors of the population should be grouped — let’s consider the Federation of Cuban Women, the Committees for the Defense of the Revolution, and clubs for workers and professionals. As a result, the structures that had previously organized institutional life were declared obsolete. Clubs for blacks were closed, because the equality of all Cubans had been officially proclaimed: only one identity, the revolutionary one, would prevail.

Nonetheless, racial inequality did not disappear altogether.

At that time, schools proliferated where young people would be molded like “malleable clay,” aspiring to their emergence as “new men” as defined by Ernesto “Che” Guevara in 1965. Many of these centers were concentrated on a small island south of Havana called Isla de Pinos (renamed Isla de la Juventud in 1978). The first Cuban black filmmaker, Sara Gómez, arrived there, camera-in-hand, to shoot a documentary trilogy depicting the experiences of these young people. In one of them, Una isla para Miguel (1968), a scene in which Rafael, a young black man, denounces the persistence of racial prejudices within the revolutionary society, has remained anthological in Cuban cinema. Facing the camera, Rafael’s gaze, like that of the young model on the cover, interrogates us, demanding action, a real change.

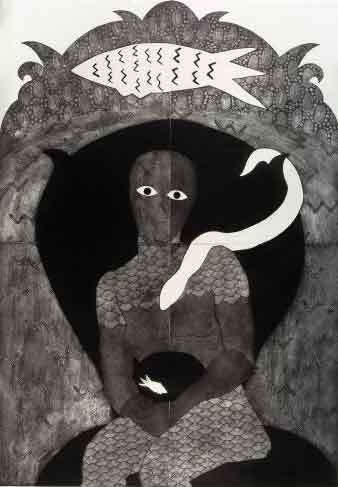

Sara Gómez is one of the maroons who never stopped fighting for social justice and who, even after her death, compels us to continue the battle. As does another great black Cuban artist, Belkis Ayón, whose work often recreated the founding myths of the Abakuá, a secret mutual aid society. From the Calabar region in West Africa comes the founding myth of the Abakuá, encoded with the discovery of the original secret —the voice of Tanze, the sacred fish— by Princess Sikan, then sacrificed and turned into a religious foundation. Since then, this society has remained closed to women, which naturally prevented Belkis Ayón from being privy to the perspective of a practitioner. Her pieces don’t reveal to us the Abakuá liturgical secret but the representation of the condition of the secret. She uses minimalist silhouettes barely revealing generic belonging, in which what’s essential is often a gaze. Furthermore, the figures lack mouths: they can’t speak. Only a thick mystery inhabits them, advancing from the hollow of the gaze towards the spectator, provoking restlessness.

Sometimes, a gaze is not even necessary. Artist María Magdalena Campos-Pons keeps her eyes closed in the polaroid series that comprise one of the pieces from When I Am Not Here, estoy allá. This message is written on her torso: “Identity Could Be a Tragedy”; but the image progressively disappears under a white spot, until it disappears almost completely in the last photo. Spectators asks themselves, what could be that “here” and “allá” (there)? — her native Cuba, the United States where the artist has lived, or Africa, which is also part of her history? The tragedy derives from the impossibility of identity, which never fully expresses everything we are.

It’s impossible to grasp the experiences of black Cuban women within a simple image, to catalog them all under an identity label. That is why we fall into a whirlwind from whose background we are absorbed by the grim look of the “Quinceañera con Kremlin,” where artist Gertrudis Rivalta alludes to a more recent reality: Cuba after the collapse of the socialist system in Eastern Europe, in the 1990s. The disappearance of economic support from the socialist bloc countries led to an acute crisis on the island, known as the “Special Period.” Since then, economic difficulties and the transformations of Cuban society have increased racial inequality, making visible a phenomenon previously circumscribed to private or family spheres. Today, the rare presence of black Cubans in spaces where the most privileged groups usually gather, attests to the undeniable existence of these inequalities.

If in the urgent daily survival there are few pathways open to the majority of blacks, we also have an invaluable capital in our maroon tradition. The maroons emancipate themselves, they don’t wait for anyone to come set them free. In the woods, they find a way to survive and defend their freedom, using whatever tools and knowledge they find along the way. They invent their own modes of subsistence.

This maronage is often transmitted by black women, from mothers to daughters, using means never mentioned in history textbooks or in famous speeches. Time and again we have sustained the home given the traditional occupations allowed to black women. María Magdalena Campos-Pons alludes to those women in “Spoken Softly with Mama,” when she reproduces old carbon plates on glass, while the artist’s ancestors seem to observe us from the bottom of the installation —always that same gaze— through photos projected on ironing boards.

The maroons continue to use whatever they find within their reach — not just to survive, but to strive. Artist Susana Pilar Delahante Matienzo created the character of Flor Elena as an avatar in the game Second Life, where she is a financial dominator (Findom). Her image was presented at the 2015 Venice Biennale in the piece “Dominio inmaterial.” The artist was able to travel there thanks to the virtual slaves of Flor Elena, who provided the funds to buy a plane ticket. The black Flor Elena, a virtual character, then had an impact on the real life of its creator, also black. Without a doubt, maroon methods. But the action is right-on; and its power, inescapable. Just like the nameless young black woman’s gaze on the cover, from which we can’t escape.

13th Havana Biennial: In Search of the Possible

The thirteenth edition of the Havana Biennial, the most important visual arts happening on the island, will be held from April 12 to May 12, with the title La construcción de lo posible (The Construction of the Possible).

Founded in 1984 with the aim of researching, theorizing, and positioning the arts of the so-called Global South —an update on the term Third World— the Biennial not only meant an opening for Cuban art, but also an alternative and legitimizing space for the artistic practices of the Caribbean, Latin America, Africa, and Asia. In recent years it has opened to other regions of the world, and has become an international benchmark.

At its start the Biennial had an open call and was a contest; starting with its third iteration, the prizes and country divisions were eliminated and the artistic selection was made based on curatorial axes related to problems of the Global South, such as: the coexistence of the traditional and the contemporary; globalization; art and its relationship to life; individuals and their memories; migration; indigenous peoples’ knowledge systems; and social imaginaries.

The thirteenth edition has challenged itself to enhance the transformational nature of art. In the face of a contemporary climate defined by armed conflicts, migration, violence, economic crises, and environmental deterioration, seeking solutions from different perspectives becomes a priority. So the primary focus of this Biennial is, from a base of artistic production, stimulating new models of coexistence, forms of community living, and networks of solidarity.

With each Biennial, Havana becomes a great cultural corridor, allowing for interaction between artists, curators, theorists, managers, and the public. Furthermore, it extends its reach beyond the visual arts, also promoting a close dialogue with music, dance, and literature. This year, its culmination will be a tribute to the “Wonder City” of Havana on the 500th anniversary of its founding.

The Biennial will convene around 200 artists from more than 50 countries, approximately 70 of whom are Cuban artists, including National Visual Arts Award winners Manuel Mendive, Roberto Fabelo, José Villa Soberón, René Francisco, Eduardo Ponjuán, Pedro de Oraá, José Manuel Fors, José Ángel Toirac, and Pedro Pablo Oliva. Exhibitions will be hosted at the Wifredo Lam Contemporary Art Center, the National Council of Visual Arts, the Office of the City Historian, Pabellón Cuba, the National Museum of Fine Arts, the University of the Arts (Instituto Superior de Arte), the José Martí National Library and the Villa Manuela Gallery at the Union of Writers and Artists of Cuba (UNEAC), as well as in public spaces throughout the capital.

One of the novelties of this Biennial will be its expansion to other provinces: in Pinar del Río, the Farmacia project, directed by Juan Carlos Rodríguez; in Matanzas, Ríos intermitentes by María Magdalena Campos; in Cienfuegos, the collective exhibition Mar adentro; and, in Camagüey, the International Video Art Festival.

In Havana, the event’s artistic map transcends institutional sites, flooding the entire city with art. Thanks to the third edition of Detrás del muro (Behind the Wall), six kilometers of the Malecón seawall will become a huge gallery. With more than 70 invited artists, passers-by can enjoy the multisensory experience in which all kinds of art are mixed with the sea breeze, tropical heat, and urban soundscape.

The Línea Street Cultural Corridor, under the direction of architect Vilma Bartolomé, is one of the most ambitious ideas: to revitalize the popular artery in the El Vedado neighborhood, beginning from the rescue of historical-cultural heritage, along with graphic interventions in the streets and buildings and updates to street fixtures.

Another Biennial offering is the Taller Chullima, coordinated by Cuban artist Wilfredo Prieto. His studio, an old shipyard on the banks of the Almendares River, will be a meeting point for creators from Mexico, Brazil, Austria, and Spain.

On this occasion the theoretical program —one of the most important aspects of the Biennial— has been organized by the Department of Art History at the University of Havana. The conferences, conversations, and exchanges with Cuban and foreign academics, essayists, and curators in previous biennials have enabled critical thinking about contemporary artistic practices, especially those carried out in the Global South and its diaspora.

This 2019 Biennial promotes art as a living event, where creation and life merge. The broadening of the event to parks, streets, and neighborhoods makes it possible to infuse an aesthetic experience into everyday life. It also provides a special opportunity to enjoy the unique vistas of 1950s-era cars and the baroque, art deco, and eclectic buildings that coexist with contemporary art.

Over its 35 years the Biennial has sought to create alternative modes for the circulation and consumption of art, which go beyond white gallery spaces and the mainstream market. It has been set up as a space for dialogue and reflections for both insiders and outsiders, a bridge between artists, critics, and academics from multiple geographies. Undoubtedly, it is a kind of creative laboratory for implementing new cartographies and alternatives for the construction of the possible.

(Español) Por el buen camino

Cuba’s most valued asset: its people

It’s already been a year since the so-called D17, a transcendental day in which the governments of the United States and Cuba announced to the world the decision to reestablish diplomatic relations and move forward in a process of normalization that leaves behind the embargo and hostility. Today the island’s market looks very interesting for US investors and businesspeople.

The University of Pennsylvania and Momentum, [email protected], in collaboration with OnCuba, organized last November a four-day trip for US businesspeople as part of the Knowledge Mission, an initiative to explore investment possibilities on the island.

Wharton has coordinated an important conference series on Cuba in which I have participated as a lecturer: the Cuba Opportunity Summit, the US-Cuba Corporate Counsel Summit, and the Infrastructure, Finances and Investment in Cuba Summit.

I had already told my friends about Wharton and Momentum, that it was indispensable for the participants and protagonists of these conferences to visit Cuba. One cannot speak seriously about a country and even less about possibilities and intentions to invest in it without getting to know it, take it in, exchange with its people. It is necessary to understand who we are as a nation, as a people, our culture, idiosyncrasy and to have contacts and talks with officials, especially with those in charge of carrying out the economic reforms and with those responsible for foreign investment.

Wharton listened and came to Cuba with a group of executives, businesspeople, investors and representatives of some of the most important US companies. I had the opportunity of accompanying them during the entire trip and during the intense meetings, getting to know them – I already knew the majority -, interacting, observing them while they got to understand Cuba. After almost a week I saw they were convinced about some fundamental things:

That it is not a question of arrogance when we say that Cuba is a marvelous, useful, fertile country in every sense. That, as I have said many times, there are countless opportunities. But Cuba is a country with very peculiar characteristics where, for example, money has less value than trust; and trust and human relations are vital to bring to fruition an investment endeavor. That a harsh and real embargo exists – they had no idea about the consequences -, with a harsh and real impact not only on macroeconomics but also on those who are worth the most: the Cuban family.

In my opinion, the in-depth knowledge acquired by these businesspeople after this visit to the island was the most important “asset” – speaking in accounting terms -, the “essential value” for the opportunities, is and will be the persons in Cuba, the people, the protagonists of the changes.

Cuba: Five Topics Worth Talking About in 2019

This new year brings several important issues in Cuba to the fore. Here are five topics that will presumably be covered extensively in the media and on the streets in the next twelve months.

1. Constitutional Reform

After months of debates and controversies, 2019 should be the year in which Cuba approves its new Constitution. Or not.

The future Magna Carta—which does not anticipate a change in the Cuban political system and follows the guidelines of the economic reforms undertaken on the island in recent years during the presidency of Raúl Castro—will be brought to vote on February 24.

Through the referendum, Cubans will decide whether to endorse or reject the text that was unanimously approved by the National Assembly of Cuba on December 22, after a process of popular consultation involving almost 9 million people, including Cuban émigrés for the first time.

Voters will answer a single question: “Do you ratify the new Constitution of the Republic?” If the “yes” vote that the Cuban government is putting forth wins, the Island will have a new Constitution to replace the current one, which was approved in 1976 and modified several times since then.

It could come into effect on April 10, following a petition by several deputies and meant to coincide with the 150th anniversary of the approval of Cuba’s first Magna Carta put forth by the island’s independence leaders who fought for liberation from Spanish rule.

If it is not ratified, however, it would open a period of uncertainty during which the next steps would not be entirely clear. In that case, the current Constitution dating back to 1976 and with several subsequent reforms, would be upheld, at least for the time being.

2. The Economy, Again

2019 does not promise to be an easy year for the bedraggled Cuban economy. President Miguel Díaz-Canel said at the end of 2018 that “the economic battle” will continue to be “the fundamental and also the most complex task” for Cuba, and that this year will be one of “organization” (ordenamiento). Priority will be given to paying off debts that the government has accumulated, over obtaining new lines of credit.

In line with Diaz-Canel, Cuban Minister of Economy and Planning Alejandro Gil called for “enhancing efficiency and productivity” in his last speech of 2018 at the National Assembly, where he assured that the island has the potential to grow by “adjusting available resources” and avoiding greater external indebtedness.

Gil predicted a GDP increase of 1.5%, higher than 2018’s 1.2%—according to data from the Cuban government—but to achieve it he said that a better investment process will be necessary, including better use of productive capacities and export diversification. Not an easy task for an economy burdened by internal obstacles, idleness, and inefficiencies, in addition to the effects of the U.S. embargo.

It will also be necessary to see how much the private sector can take off given the new regulations as of December 2018, and what it is capable of contributing to the Cuban economy as a whole, despite endemic impediments such as the lack of a wholesale market and the impossibility of large-scale importation.

3. US-Cuban Relations: Stand-by or Rollback?

Although 2018 ended on a less-tense note given the agreement between Cuba and Major League Baseball (MLB)—allowing Cuban players to legally play in American baseball leagues—and the approval of the U.S. farm bill Cuban trade provision, this new year does not exactly augur hope for bilateral relations.

Cuba is not a priority on the current U.S. government’s agenda, but when it does arise, it is not cause for celebration. In addition to maintaining the embargo and the hostile discourse in Washington—and the corresponding response by Havana—the measures taken by Donald J. Trump in his two years in the White House have put the brakes on the approach put forth by Obama and Raul Castro, and have been a bucket of cold water for those who are pro-engagement.

But in the coming months the situation could worsen, at least according to some analysts’ predictions, because 2019 is a pre-election year.

Seeking votes in Florida, Trump could increase restrictions on travel by Americans to Cuba and include more Cuban hotels and entities on the “black list” of places prohibited for US citizens who visit the island.

The blow could even affect the historic agreement between the Cuban Baseball Federation and the MLB, an agreement that Senator Marco Rubio and other politicians opposed to rapprochement with Cuba have already threatened to torpedo.

4. The 5 Million Tourists

Cuba waited for them in 2018, but they did not come. After a first semester with a fall of 6.5%, last year’s tourism forecasts were reduced by the Cuban Ministry of Tourism (MINTUR), which deployed an intense campaign to reverse the situation in the subsequent months and, above all, to make the expected jump in 2019.

In 2018, the Island received more than 4.7 million visitors, a new record, with Canada once again the primary market. Cruise ships provided a buoyant increase in arrivals—mainly to the ports of Havana, Santiago and Cienfuegos—and allowed Americans to circumvent the Trump administration’s measures against travel to Cuba.

For 2019, MINTUR has an ambitious plan: 5.1 million visitors, more than 5,000 new rooms throughout the island, and more cruise trips. In addition, it foresees diversification with a marketing of Cuba beyond “sun and beach,” with the promotion of ecotourism, health tourism and major events as emerging modalities, the latter mainly in Havana, which will celebrate 500 years since its founding and will host the 39th International Tourism Fair (FitCuba 2019).

But these objectives are not enough. The increase in tourists must be coherently accompanied by another more important one: income. Only then can tourism boast of being the locomotive that the Cuban economy needs.

5. Five Centuries of Havana

Havana will turn 500 on November 16, 2019, following the tradition of commemorating the founding of the city at its current site and not at its first settlement, on the south coast of the island. With this, Havana will be the last of Cuba’s seven founding townships to celebrate its half-millennium.

The Cuban capital is already in countdown mode and launched a campaign in 2018 led by the Office of the Historian and the municipal government, including construction, and social and cultural activities throughout the year.

Restoration of buildings and emblematic streets, celebrations and cultural events, and construction of new houses and hotels, are all part of the program, which will culminate in the celebration of the anniversary in November, at which the King and Queen of Spain are expected.

Although it is impossible to erase the many problems accumulated by the city over the years in just a few months—construction, sanitation, transportation, lighting—Dr. Eusebio Leal, Official Historian of the City of Havana, called upon Cubans to take advantage of the anniversary’s momentum to consider the 500 years not as a goal but as an opportunity to continue working to “change the face of Havana.”

Whether or not that is fulfilled, from now through November much will be said about the five centuries of the beautiful Cuban capital.

Cuba’s unique appeal

Why this tiny island captivates so many different people?

“Every time I go to Cuba, I come back sounding like a tourist brochure. I bore my friends by counting the ways I love the improbable idyll,” essayist Pico Iyer once wrote. I know how he feels. This troubled, iconoclastic island of tropical charms has haunted me like a sweet dream for three decades.

The potency of Cuba’s appeal is owed to a quality that “runs deeper than the stuff of which travel brochures are made. It is irresistible and intangible,” notes Juliet Barclay. —Arnold Samuelson recalled his first visit to Havana in 1934: “everything you have seen before is forgotten, everything you see and hear then being so strange you feel… as if you have died and come to life in a different world.” The city’s ethereal mood, even more pronounced today, finds its way into novels. “I wake up feeling different, like something inside me is changing, something chemical and irreversible. There’s a magic here working its way through my veins,” says Pilar, a Cuban-American character in Cristina García’s novel Dreaming in Cuban.

Virtually every North American I know who’s been to Cuba has returned home beguiled, and to a degree that few other destinations inspire. This despite six decades of negative portrayal by U.S. administrations and embittered objectors propagating delusions like dark hot-house orchids. Regrettably, Cuba is all that they say it is… and yet, in its own cryptic way, none of those things!

Explaining Cuba’s unique appeal is like explaining the magic of sex to a virgin. Barclay had it right. It can’t be seen, touched or photographed, although the physical backdrop—the tangible—is integral to the visitor’s emotive experience.

Your first reaction is of being caught in a surreal 1950s time warp. Fading signs advertising Hotpoint and Singer conjure the decadent decades when Cuba was a virtual colony of the United States. High-finned, voluptuous dowagers from the heyday of Detroit are everywhere, too: chrome-laden DeSotos, corpulent Buicks, stylish Plymouth Furies and other relics of 1950s ostentation, when American cars reflected the Hollywood zeitgeist of excessive wealth, fantasy, gaudiness, and sex with which Havana was at that time synonymous. All the glamor of an abandoned operatic stage set is there, patinated by age.

Strolling Havana’s streets you sense you are living inside a romantic thriller. You don’t want to sleep for fear of missing a vital experience. Before the Revolution, Havana was a place of intrigue and tawdry romance. Batista’s Babylon offered a tropical buffet of sin. Spies and conspirators lurked in the shadows. It’s still laced with sharp edges and sinister shadows. The whiffthe intimate of liaison, of conspiracy—is still in the air. (Though less so now than in 1992, when I first traveled to Cuba.)

There’s a little bit of Narnia to Cuba, and plenty of Alice in Wonderland. What sends visitors into flights of ecstasy is their sensation of having stumbled upon a bewitchingly otherworldly domain. Sure, you’re only 90 miles from the neon-lit malls and McDonalds of Florida, but you’ve crossed an arcane threshold to discover an unexpectedly haunting realm full of eccentricity, eroticism, and enigma. As soon as you step from the plane, you succumb to the fervid isle’s Delphic allure. It’s impossible to resist its mysteries and contradictions.

I first arrived by sea at night, like the smuggled human freight in Ernest Hemingway’s To Have and Have Not. Come dawn, I leaned against the rail with the wind whipping my hair as we passed beneath an imposing castle looming over the harbor entrance. Winston Churchill had felt “delirious yet tumultuous” as he approached Havana by sea in 1895. “Here was a place where anything might happen. Here was a place where something would certainly happen.” I, too, felt a welling sense of possibility and adventure, almost sexual in its intensity.

Seduction comes quickly in Cuba. Often, quite literally. “Dark-eyed Stellas light their fellas’ panatelas,” songwriter Irving Berlin penned of Havana, although seduction is a national pastime enjoyed by both sexes. It is the free expression of a “high-spirited people confined in a politically authoritarian world,” noted Argentinian journalist Jacobo Timerman. For visitors, the joyous eroticism—part of a broader contagious gaiety—that pervades Cuban life is titillating, liberating, and luring in equal measure.

The Revolution has equalized the sexes to a far greater degree compared to the UK and, especially, the USA. In many ways, Cuba is leagues ahead in our age of political correctness. And yet… Cubans appears deliciously, defiantly démodé in ways visitors least expect.

Life here seems a paradox. Socialism and sensuality. Caribbean communism. Cuba is, after all, a tropical nation—and Latin at that. Nightclubs are easy to find, throbbing with sounds from jazz and reggaeton to son and salsa. Hints of Havana’s old sauciness linger on, too, at cabarets such as Tropicana, the prerevolutionary open-air extravaganza now in its eighth decade of stiletto-heeled paganism.

While most Cubans lack the money for such venues, they’re inordinately rich in spirit, kindness, and social bonding… a reminder that life can appear fuller when you have fewer things. A reminder of what, above all, I so love and admire about Cubans and Cuban community.

I cherish how they wear their hearts and their lives on their sleeves. How they look you in the eye and engage you directly. Boldly self-assured, there’s no reserve. No sense of being judged. Black, white, and every shade in between live harmoniously as equals with self-assured ease. It’s uplifting. And forget the insularity of the USA’s concept of “a man’s house is his castle.” An average of fifteen non-family members enter any one Cuban home each day! Doors and windows are flung open so that Cubans live their lives in full view, tempting you to peer in through the rejas—grills—the way one is irresistibly drawn to sneak a glance when the neighbors forgetfully leave their drapes open at home. Even the shutters of the hogar materno, the local maternity home, are wide open, revealing nine-months-pregnant women in nightgowns lounging on beds, nursing swollen bellies while paddle fans stir the air. You feel like a voyeur on the set of a Fellini movie.

Throughout Cuba, women sit on door stoops or pull their sillones (rockers) onto the sidewalks to share the day’s gossip… the men drag tables into the street and play dominoes shirtless… and laughing, happy children play freely outdoors, reminding James Mitchener of “a meadow of flowers. Well nourished, well shod and clothed, they were the permanent face of the land.”

Then there’s the resourcefulness, ingenuity, and indefatigable good humor in the face of persistent shortages, lamentable decay, and unsettling sorrows. There’s a beauty in the Cubans’ non-materialist innocence (though that is rapidly changing), and the fun-loving way they turn adversity on its ear, eliciting simple pleasures out of thin air, swigging tragos of añejo rum, dancing hip-swiveling, groin-to-groin rumbas at impromptu cumbanchas (street parties). Everywhere you go you’re surrounded by sexy rhythms. As you walk down the street, Cubans you do not know will urge you to join in. The music is cranked up until you think the beer bottles will get up and dance. Friends and neighbors arrive, take your hand, and kiss your cheeks. You’re pulled bodily into the street to dance. It’s the same all over the island. Cubans you’ve met moments before embrace you, call you amigo, and invite you into their homes. You’re fêted with human goodness with no expectation of reciprocity.

It’s hard to believe that the U.S. government’s Trading with the Enemy Act is directed at these genteel and generous people. How often have I teared up and cried, dancing with the enemy, as it were?